1940s - Bowling at the Balboa Pavilion.

Because the Pavilion is anchored on a narrow strip of sandy waterfront, most of the building was supported on wooden pilings which extend over the bay. In 1947, the wooden pilings deteriorated to the dangerous point and the building began to collapse into the bay.

In 1947 or 1948, the Gronsky family purchased the Balboa Pavilion primarily to operate a sport fishing landing and to continue leasing the upstairs.

However, rumors circulated that the Pavilion, which was run down and in disrepair, would be leveled and transformed into a boat yard. But according to Art Gronsky, “We assured everybody we would keep the Pavilion and make it better. When we reopened it in 1949, it was quite an event for Balboa.”

Because the building was in such poor condition, the Gronsky’s obtained the building at a very low price. To rectify the deteriorating twenty-six original wooden pilings, eight large, concrete pilings were installed, a Hurculean task. Workers pushed wheel-barrels full of concrete across scaffoldings to install new concrete pilings. The result was a newly fortified, element-resistant city landmark. Additionally, the lower walls of the building were also rebuilt to be structurally sound.

In 1949, the Gronsky reopened the building.

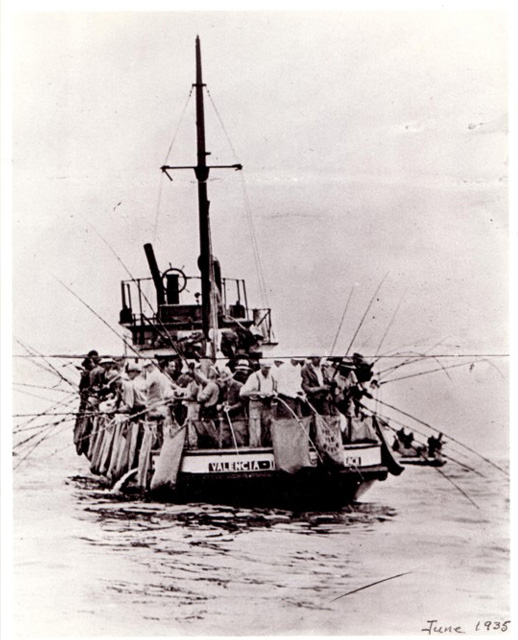

At first, the Gronskys did not own their own fishing boats. But they allowed other boat owners to run their boats out of the Pavilion on a percentage basis. The Gronskys converted the Pavilion’s only boat, the “Crescent,” into a bait carrier and hauled bait the Pavilion fishing boats and the other eight fishing landings in the bay.

But the private boats had to obtain their bait from bait tanks at the Pavilion, the only harbor bait provider at that time. During the height of the Albacore season, boats lined up a quarter of a mile, clear back to Bay Island, to purchase bait. Later, competition emerged when other boats sold bait at the end of the Jetty, ending the bait monopoly.

The Gronsky’s continued speed boat rides. Their boat was the “Leading Lady.” However, a speed limit was imposed in the bay. Therefore, the “speed” part of the ride had to wait until they exited the bay and entered the ocean.

According to Art Gronsky, the bowling alley, archery, and pool table continued but, due to suspiciously low monthly percentage checks amounting to less than $20.00, the Gronskys switched to a fixed rate rental. This caused the business owner not to renegotiate the lease. According to Gronsky, the owner chopped each bowling lane into three pieces, slide them out of the side of the building and into a truck and, he heard, reinstalled them somewhere in Arizona.

By 1949, a gift shop and the “Sportsman Wharf” restaurant replaced the amusement center. Further, the upstairs was rented to a “Skil-O-Quiz” bingo parlor. As many as 500 participants at a time played bingo. The prizes were merchandise, not money. However, a nearby place would trade the merchandise for cash. In 1952, the bingo was deemed too wicked, was outlawed, and the sheriff closed the establishment down.

In 1954, Gronsky instituted a shell museum upstairs. Gronsky purchased one of the world’s most extensive private shell collections from the estate of Fred Aldrich, who had lived on Bay Island (an exclusive private island on the bay which allows no vehicles). The museum displayed over 2.5 million shells. Later, Gronsky added shell fish store. Eventually, due to vandalism problems, the shell fish collection was donated to Bowers Museum in Santa Ana.

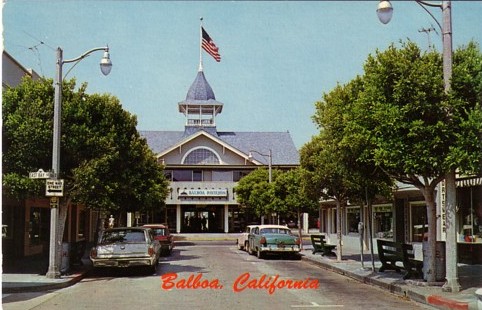

1950s - Balboa Pavilion

In 1961 the Gronskys sold the Balboa Pavilion to Ducommun Realty Company of Los Angeles. Edmond G. “Alan” Ducommun, who enjoyed the Balboa area as a child. His “mission” was to restore the building. Ducommun generously invested an estimated one million dollars into the property. He remodeled and restored the exterior of the building, including the blue shingled roof, gray paneled walls, and distinctive cupola. This helped restore the building to its original 1906 look.

According to Bill Ficker, an architect who worked on the year long renovation, “They did it because they loved the Pavilion and they thought it was a landmark worth being preserved.”

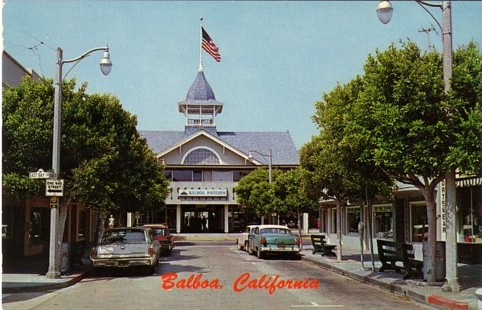

1960s - Balboa Pavilion

From 1962 through 1970, the upstairs of the Pavilion housed the Newport Harbor Art Museum. Thirteen audacious ladies who started the Newport Harbor Art Museum asked Mr. Ducommun if they could use the 8,000 square foot upstairs -- for free! Mr. Ducoomun kindly agreed. According to Betty Winckler, the founding force behind the museum, in a magazine article:

“I called Mr. Ducommon at his home in Portuguese Bend at 7’oclock in the morning and I guess he couldn’t believe what he heard – some women he didn’t know wanted to use his building for their art museum, for free.."

"The building was in pretty flaky condition,” according to Ms. Winckler.

We agreed to make a few improvements on the second floor – a heater for winter, vents for summer, and restrooms.

“Finally, the big day came, and on October 15, 1962, I proudly turned on the switch lighting the Pavilion Art Museum for our first show. Artist Miller Sheets was the guest lecturer…”

In 1963, Ducommun added 1500 lights to the buildings exterior at the suggestion of a former restaurant lessee. Even today, the Pavilion continues to light up the night with its 1500 glowing light bulbs. These lights, along with the Cupula on top of the building, incidentally serve as a navigation beacon for night boat travelers.

In 1968, the Pavilion was named a California State Historic Landmark. The Pavilion is also listed in the National Register of Historic Places, which is the highest honor a historic building can receive.

The Balboa Pavillion is state historical landmark #959 and national historic landmark #84000914.

From Left to Right - Evelyn Hart, Phil Tozer, Marion Bergeson, James Shafer

Alan Ducommun admits: “I think when I bought it, I was leading with my heart instead of my business head.” After ten years of ownership but not financial success, he was ready to sell the Pavilion.

In 1969, Davey’s Locker Inc., a sport fishing operation, under the business leadership of its president, Phil Tozer, purchased the Balboa Pavilion to provide a permanent terminal for the expansion of its Catalina Island passenger service. Tozer undertook to refurbish the building’s interior to reflect the turn of the century architecture. With no interior architectural plans and very limited photographs to refer to, Tozer, nevertheless, sought to create an authentic 1905 interior. He searched out a lot of old Victorian homes and bought what they call “architectural debris” (old parts of Victorian homes that were saved and reused). Notable additions included the beautiful, monumental oak staircase, six authentic oak doors, oak chairs sitting on antique rugs, ornate tin ceiling, leaded glass mirrors, antique furnishings, hall trees, twinkling chandeliers, charming photographs, an authentic waterfront saloon with a solid oak back bar as well as many others. Phil Tozer further invisioned and created a multiuse marine recreation facility.

On May 20, 1980, the Balboa Pavilion Company branched off from Davey’s Locker and took over ownership of the Pavilion.

In 1981, the Balboa Pavilion was designated as a California Point of Historic Interest.

In short, a long succession of owners have sought to preserve its basic structure, retain the Pavilion’s beautiful Victorian lines as well as its authenticity.

The Pavilion is a classic example of the turn-of-the-century waterfront pavilions and continues to be the center of Newport Beach activity.

The Balboa Pavilion “is the city landmark,” according to Ficker. “Every painter has painted it and every photographer has photographed it. It is the grand dame of focal points.”